Deciphering Applications in Chen Taijiquan

First a disclaimer: These guidelines are designed for those students who do not have the benefit of a qualified teacher. This has been the case with since leaving the Chen Village (chenjiaguo) thirty years ago. After long years of practicing and researching on my own, I believe I have come up with a series of guidelines that may be of use to advanced practitioners.

It should be mentioned that this article will be focusing on the First Form of the Old Frame (laojia yilu). Most of the guidelines should hold true for the other forms but I haven’t done an in- depth investigation of them yet.

It should also be mentioned that applications will vary based on the lineage followed by the practitioner. All the four current Grandmasters (Chen Xiaowang, Chen Zhenglei, Zhu Tiancai, and Wang Xian) perform the routines (taolu) quite differently. This is a reflection of their individual growth and personalities as well as the qualities or techniques that they have chosen to emphasize. I personally am part of the lineage of Grandmaster Chen Xiaowang so I am basing the individual applications in this article on the way I (he) performs the movements. Nonetheless, the basic guidelines should still apply for all.

Caution:

With the advent of YouTube more information is available now than ever before. However, one should be cautious when studying online videos. Some of the applications in these videos ring true, especially those of the Grandmasters. However many application videos are merely guesses by uninformed students or teachers. Hopefully, with the help of these guidelines you will be better able distinguish the true from the false.

Chen Taijiquan is first and foremost a martial art.

This principle influences every aspect of the Chen System. It is the reason the postures and movements are more complicated than other styles of Taijiquan which emphasize health benefits. Being a martial art rather than a health exercise is also the reason that the routines contain movements that require energy release (fajin ). Chen Taijiquan was developed at a time when skill with empty hands and traditional weapons were often necessary for survival. However, later forms of “T’ai Chi” developed in the modern era when martial arts were used more as a form of cultivation. By removing the martial elements of Chen Taijiquan, these subsequent styles became more of a Qigong practice than a martial art. Chen Taijiquan, on the other hand, contains all the health giving benefits of the later styles while still retaining its core as a martial art.

Chen Taijiquan is primarily a grappling art. That is to say, most of the techniques are meant to be applied at close quarters to lock, throw or push the opponent. This is the reason for the emphasis on slow motion movements, precise weight shifting and rooted-ness. One must have perfect balance and root in order to throw an opponent without being thrown oneself. On the other hand, striking movement - punches, kicks, elbows etc. - should be done quickly while releasing energy (fajin). Once a striking technique is learned properly, there is very little value in practicing it slowly.

Why Decipher Applications?

Chen Taijiquan is a complex martial art system. The ultimate goal is to be able to use it as a form of self-defense or personal combat. The traditional way of training is long and arduous. There are no shortcuts and one can not rush the process. However, it is sometimes helpful to get a glimpse of the final destination. Deciphering applications is like finding clues that help to eventually solve a mystery. Demonstrating applications can also be a great motivator for students allowing them appreciate the depth of the system. For more advanced practitioners, being able to decipher applications can indicate that one has reached a higher level in their practice.

Why Can’t I Learn Applications Right Away?

Anyone who has studied Chen Taijiquan has wondered, “What is this move for? How could I use it against an opponent?”. Traditionally, teachers in China have been reluctant to reveal applications to any but their most trusted disciples. Students are admonished to practice the form and not think about applications. Many students have practiced for years without being shown a single application. Students in the West are often not as patient. Many masters who give seminars outside of China have acceded to their Western students and begun showing a few applications here and there.

Those who practice for a long time will realize the wisdom of the traditional teaching method.

While it is a good mental exercise to try and discern applications, one should not focus on them to the detriment of form practice. Focusing on what you think may be application of a movement can actually change the way you practice that movement. In the long run, this will hinder your progress. One should never alter the performance of a movement in order to conform to some preconceived notion of what the application may be.

Rushing to learn an application can also be extremely frustrating. Even after being shown an application in detail, most beginners will be unable to apply it effectively. This is because their practice of the routines, especially the foundation exercises, is not at a high enough level. However, being shown a technique and then being unable to apply it is a good way to demonstrate the importance of perfecting the Silk Reeling principles and taolu movements. This was my experience while in Chenjiaguo. After much pleading, our teacher agreed to show us one application. He applied it everyone in the class causing all of us to yelp in pain. Whet it was our turn however, none of us could make it work. I realize now that this was because none of us had reached a high enough level of training (gongfu).

Guideline #1: There are both obvious and hidden applications.

In order not to hinder the Qi development, the form should be practiced according to the principles and one should not place a limit on each movement by focusing on a particular application. Every movement has many possible applications. Considering each a part of a circle, one realizes that all points on the circle can represent a particular application., depending on the situation. One should learn the method, not its manifestation. (Chen, Zhenglei, 1999)

Make no mistake, the applications in Chen Taijiquan, are purposely hidden in the empty hand routines (taolu). This practice is universal in Chinese martial arts. In China, knowledge has always been power so the secrets of a martial art were jealously guarded. Moreover, there was very little privacy in ancient China, so martial arts masters had to devise ways to practice in public yet still retain their secrets. Therefore, they developed empty hand routines which contained fighting techniques hidden in plain sight.

Some applications are rather obvious, such as the uppercut and knee strike in

Buddha’s Attendant Pounds the Mortar. However, it is a mistake to believe that the obvious applications are the only ones contained in the movement. Most movements have additional “hidden” applications that are only revealed once the student has truly mastered the movement and thoroughly understands and applies the principles of Chen Taijiquan.

Sometimes there are quite a few applications for given movement, sometimes there is only one primary application. For more complicated movements such as the above mentioned Buddha’s Attendant, there are applications for many of it’s constituent parts. One master has demonstrated as many as fourteen individual applications in the

Buddha’s Attendant alone. On the other hand, relatively “simple” movements like

Lazily Tying Clothes has one primary application for the complete movement which is not at all obvious.

One should always try to look beyond the obvious applications. Examining a movement more deeply while properly applying Chen Taijiquan principles can often yield surprising results.

Guideline #2: An application only works if done exactly like the form.

However, Chen Style is characterized by it’s external movements, which are much more intentional for martial arts purposes. By this I mean the movements are exactly as you would use in martial art application.

You do not have to move your hands slightly higher or lower; your hand shapes, your finger shapes and your body can be used just exactly as in many martial arts practices. It also contains many force delivering movements (fajin). Peter Wu, Tai Ji Magazine, August 1995

For an application to work correctly, it must be performed exactly like the taolu posture. If you have to vary the movement to make the application work, it is probably not correct. For example, the application of

High Pat on Horse must be performed exactly like the taolu movement including the step up and back, pivot and even the finishing posture with the left knee turned outward. When done properly, everything falls into place and it works effortlessly. If an application requires such a major alteration that it no longer resembles the original posture, chances are that it is not correct. Forcing a posture to fit a certain scenario is like forcing a round peg into a square hole. You have to keep an open mind when deciphering a movement- the application is what it is, not what you want it to be.

Guideline #3: Movements are repeated for a reason and the application is different for each one.

“

Look to the principle behind the movement.”

Movements that are repeated are done so for a reason.

Six Sealing, Four Closings is performed several times at different parts of the routine. Each time it is performed a little differently. Why? Because each variation deals with a different angle of attack. For example, one application is from a stationary position with the right foot and hand towards the opponent. Another variation sweeps to the left while stepping forward with the right foot. Yet another variation applies a qinna lock on the right side with the left foot forward and then steps forward with the right foot to finish. Though each variation ends with a push (an) it is a mistake to think that this means they are all the same. One needs to look closely at each repetition of a movement to see it’s unique qualities.

Other movements are repeated several times in sequence.

Transporting Hands and

Flip and Whirl the Forearms are repeated because they counter for both right and left hand attacks depending on which side is forward. It is helpful to remember while learning and practicing the taolu that everything is done for a reason and there are no empty or transitional movements. This is part of the genius to be found in the construction of the Chen Taijiquan routines.

Guideline #4: Applications must work from an attack.

Most applications will be in response to right side punches and kicks In China, as in the West, there has always been a bias against left-handedness (in the West, the left side was called “sinister” which still has a negative connotation today ). Most martial arts begin with right sided attacks (just as Bruce Lee later advocated). Therefore to begin deciphering a movement’s application, it is best to start with responses to right side attacks. If an application works against a right handed attack then it is probably correct. From there, see if can also be applied against left side attacks. Some applications work equally well against both right and left attacks. If an application absolutely will not work against a right side attack, you can begin to explore it’s effectiveness against a left side attack. However if appears a technique will only work against an initial left side attack, it is best to explore further. A prime example is

Six Sealings, Four Closings. At first it seems that it only works against a straight left punch. Unfortunately, this usually results in the defender pulling and dragging the opponent’s arm without really controlling them. Unable to make the initial contact work, many skip right to the obvious technique, the push. This is wrong.

Six Sealings, Four Closings is designed to counter a right hand punch. Used with proper Silk Reeling energy, the initial downward movement (cai) is effortless and leaves the opponent unable to attack further (sealing the six means of attack - hands, feet, elbows, knees, shoulders, hips) or escape (closing the four directions). The lock is so effective that the push is almost unnecessary. However if the opponent is pushed, they have no way to fall safely and are likely to be injured. Add to this energy release (fali) during the push and the counter becomes devastating. Therefore remember, the easy answer is not always the correct answer.

A few applications are designed to counter a right side attack followed immediately by a left side attack but not many. There are also kick defenses. Most are designed to counter low level kicks as Chinese martial arts have always understood the impracticality of high kicks. Although the Chen Taijiquan routine contains kicks that appear to be aimed at head level these are used to develop flexibility, speed and strength. In combat, the kicks in Chen are delivered below the waist and some are not actually kicks at all.

Guideline #5: The beginning of a movement’s application begins where the previous movement ends.

Looking at the beginning posture of one movement (ending posture of the previous movement) can give you some clues as to what type of attack it is designed to counter. The application for

Six Sealings, Four Closings begins with the final position of

Lazily Tying Clothes. It is here that the right hand (the guiding hand) makes contact with an incoming right hand punch and begins guiding it downward to the left hand (the attacking hand). This is the beginning of the counter which ends when the opponent is incapacitated.

Six Sealings ends/

Single Whip begins with both hands extended in a push. The obvious attack is not a punch or kick but a double wrist grab. In this scenario the counter is devastating. However, trying to use

Single Whip against a punch or kick will not yield the same results. By the same token, most applications are not defenses against grabs. If a posture begins with a parry and you can only make it work from a grab, it is probably not correct. Additionally, if one has to begin from a position different from the end point of the previous movement, the application is probably not correct.

Guideline #6: Each Movement is Complete in Itself.

Movements in the routine are not designed to be linked together. The application of one movement is not connected to the following or previous movement. One cannot combine

Lazily Tying Clothes and

Six Sealings, Four Closings as a single application. Each movement has it’s own beginning and end and they are not designed to be combined. The often told tale of a routine being designed to fight multiple opponents is a myth. The applications of the routine’s movements are designed to counter a single attack. Once the practitioner has mastered Silk Reeling energy, Push Hands sensitivity, and applications, he or she is better equipped to handle multiple opponents but this is not what the routines are designed for.

Guideline #7:Proper timing of the movement is essential.

In

Lazily Tying Clothes, the movement begins from the ending position of

Buddha’s Attendant with both hands at the waist. From this position, the right hand (the guiding hand) sweeps in a clockwise circle to contact the incoming punch while stepping to the right. It is essential that the right step be completed at the exact moment the punch is handed over to the “attacking hand”, in this case the left. If the step is not completed then the opponent’s leg is not blocked leaving the defender open to a follow up left handed attack. However with the opponent’s leg blocked and the attacking hand utilizing Silk Reeling energy, it is easy to pull the opponent forwards and off balance. The right hand then sweeps across to the rear of the opponent’s right shoulder for the throw. Without the proper timing of the right hand and foot, the application will not work.

Guideline #8: Applications should be effortless

Only proper use of Silk Reeling Energy (chansijin) will make an application work properly.

When used correctly, the application will feel effortless. Most beginners cannot make applications work, especially effortlessly, because they have not mastered chansijin. If you have to pull, jerk or wrestle with the opponent, chansijin is not being properly applied. Done correctly, the application feels like you have done nothing yet the opponent flies across the room. After such an event, it is even common to ask your partner if they are faking because you feel like you have done nothing at all. Having been on the receiving end of a properly executed application, I can assure you that the result is genuine. I have been tossed across the gym by my apprentice who is less than half my weight. She didn’t feel like she had done anything yet there was nothing I could have done to stay on my feet.

Guideline #9: Correct applications should not depend on fajin.

Making a counter work slowly and effortlessly is the proof of a properly deciphered application. A counter-attack can be enhanced by releasing energy (fajin) but should not depend on it. If an application can be successfully done slowly, it can be done quickly. The key is proper positioning, not force. If an application is properly applied, there is nothing the opponent can do to escape. Chen Taijiquan stresses the concepts of softness, relaxation, proper posture and the spiraling motion of Qi. These qualities are necessary for success. Relying only on fajin alone makes Chen no different from an external style like Shaolin. Obviously kicks and punches should be performed with fajin as doing them slowly all the time is counter productive. Of course fajin practice is very important and that every movement in the taolu can be practiced with a release of energy. Solo form practice provides a safe way to develop and apply explosive energy. Many of the applications can be very dangerous, even when done slowly. Sometimes the risk is so great that one should not complete the movement because there is no way one’s partner to fall correctly. Practice slowly at first. If one’s partner knows how to fall and how to protect themselves by cooperating, then you can slowly start adding in fajin. Correct applications can make use of energy release but they should not be dependant on it. If an application requires muscle, speed or explosive energy to work, it is probably not being performed correctly.

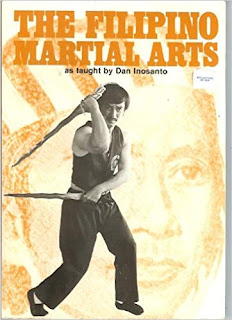

Guideline #10: Pushing Hands does not teach applications.

Pushing Hands is not the be all and end all of Chen applications. It is only a drill albeit an essential one. It teaches the vital skills of “listening” and “sticking” and requires a great deal of time and practice to master. It also allows one to practice the first four “Energies” - peng, lu, ji, an - against an opponent. The higher levels of Chen Taijiquan Pushing Hands; Ding Bu (fixed step) Huang Bu (single backward/forward step), Da Lu (moving step, deep stance), Luang Cai Hua (free step, double handed) and San Tui (free pushing) greatly increase the ability to apply applications properly. These exercises help to instill the principles of relaxed power. Although there are many uprooting and throwing techniques possible in Pushing Hands practice its purpose is not to defeat your opponent (or to stroke your own ego) but to reveal any weaknesses in your gongfu. Once the weakness detected, one returns to the taolu to correct it. Then one returns to Pushing Hands to confirm the correction. When another flaw is discerned, one returns to the routine and so on. This practice ultimately increases ones combat skill. It also demonstrates the balance of Yin and Yang which is the core of Chen Taijiquan. No one practice is more important than another. One should not practice Push Hands to the exclusion of the taolu. As my Filipino Martial Arts teacher used to say: “Learn the drill. Master the drill. Forget the drill”. The goal of Chen Taijiquan is to be spontaneous and natural during combat. Pushing Hands is only one component of that journey.

While there are many unbalancing and throwing techniques in Push Hands, these are more a demonstration of principles than actual applications of taolu movements. When attempting to decipher applications it is my belief that if an application will only work from Pushing Hands position, it is probably not correct. This is what I call “cheating” It is very doubtful that anyone will ever attack you with their arms bent in front of their chest and allow you to place both of your hands on one of their arms. In actual combat, you may come in contact with the opponent’s punch or kick for a fraction of a second. At that point the qualities of sensitivity and relaxation as well as the 8 Energies learned in Pushing Hands become invaluable. Pushing Hands should be viewed as method to increase the effectiveness of applications but it does not teach the applications of the individual movements.

One Step on the Journey

Deciphering individual applications is only the one step towards mastering the martial side of the Chen Taijiquan system. Once you have deciphered the individual applications, the next step is to group them together by the attack. For example, there are many counters to punches, kicks, grabs and pushes. However, the angle, height and direction of the attack can vary significantly. In such cases, having only one response is going to be insufficient. It is important to understand that varying angles of attack will affect the response. For example, a chest high right hand punch can be successfully directed “into emptiness” using the basic hand position and weight shift found in “Buddha’s Attendant Pounds the Mortar”. However, what if that incoming punch is directed low, or is a hook punch or uppercut? Each different angle of attack must be met by different technique. One response will not work against all situations. There is no one-size-fits all response. At this point you must use the application that is most appropriate.

Chen Taijiquan is based on Daoist philosophy. The goal in Daoism is to return to a state of naturalness or spontaneity. The same is true of Chen Taijiquan. With many years of dedicated practice, one hopes to reach the state of Taiji; the Grand Ultimate (also known as the One). At this stage, Chen Taijiquan becomes completely natural and spontaneous. After a while, rather than using an entire taolu movement to counter an attack, one is able to use Taijiquan principles to defeat it. At this point, the counter becomes so spontaneous and natural that it is difficult to tell which posture is being used. “First you find the application in the movements and then you find the movements in the applications.”

Conclusion

I hope these guidelines will be of some help to you as you continue your journey into the mysteries of Chen Taijiquan. I have constructed them to the best of my ability based on what I have discovered so far. Over time, with more practice and experience, these guidelines may be changed, refined or even expanded. If the reader can provide further insights or should disagree with the content, I would be happy to enter into a constructive dialogue. Please contact me at xilin.martial.arts@gmail.com